chapter4

IV. The Moral of the Lower Class

A. Hellenistic Age

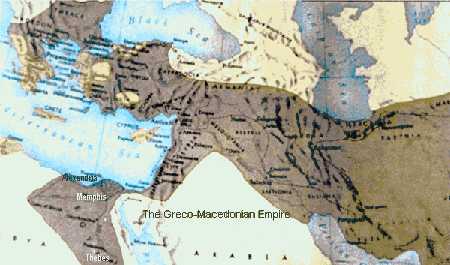

While the Greek cities-states battered one another in the fratricidal

warfare, a new military power was rising in the north – Macedonia. The

Macedonians still were semi-nomadic Aryan tribes, who followed the Dorians and

Ionians into Europe. To the fourth century BC, the Macedonians multiplied in

such degree that their mountainous territory could not properly support them. In

359 BC, twenty-one-year-old Philip II became the king of Macedonians. He had

spent three years as a hostage in Thebes where he learned the latest military

strategy and tactics, and weaknesses and strength of the Greek city-states. He

reorganized the Macedonian chieftains into an efficient officer corpus and

converted Macedonia into a well-established hierarchical bureaucracy, which

could maintain a well-trained army. His patience and unscrupulousness was

rewarded and, in 338 BC, at Chaeronea, the Macedonian army decisively defeated

the Greek confederates. In this battle, the old Hellenic urban culture has died

and the Hellenistic urban culture was born.

The decline in the civic responsibilities and the inability of the Greeks to

rise above their local interests (which were represented by the city-state

governments) to the level of the national interests and create a federal

government led the Greeks to this rapture. The federal government, as a fair

representative of the newly developed interests, would end the fratricidal

warfare, promote economic well being, and protect the Greeks from hostile

States. However, the Greek democracy could not yet learn how to balance the

interests of the industrial middle-class and the agrarian aristocracy.

The Greeks did not respond to the Macedonians as they had earlier fought with

the Persians because the quality of their citizenship had deteriorated. Pericles’

ideal of citizenship dissipated as the Athenians continued to neglect the common

interests and concentrated their efforts on their private affairs or sought to

gain profit from a public office. After the defeat in the Peloponnesian War, the

middle-class of the Ionian city-states was weakened by the constant scramble

with local aristocracy. Moreover, the Ionian confederation was dissolved and the

new, Pan-Dorian-Ionian confederation was very weak because the agrarian and

industrial interests were too polar that they could be solved peacefully.

It is a well-known fact of the human nature that the individual’s attraction

becomes weaker in proportion to the distance of the attractive object. The same

principle can be applied to a person who is more attached to own family than to

own neighborhood, to own neighborhood than to the entire community. The same

principle can be applied to the people of each city-state, who tend to feel a

strong bias toward their local government and a strong prejudice against the

federal government, unless the latter would provide a greater benefit than the

local government. However, the confederation under the leadership of the

agricultural states could not provide the greater benefit to the industrial

states. This stalemate had resulted in the situation that every local government

asserted its sovereignty and, therefore, the confederate army was a collection

of divisions that could act, as a united force only when there was agreement

among the local governments. It meant that the army spent too much time trying

to coordinate own actions, and thus, was ineffective in the struggle with the

autocratic Macedonian army. The defeat was inevitable. In the aftermath of this

event, the world of the small and self-sufficient city-states ceased to exist

and the Greek urban culture was taking a different shape.

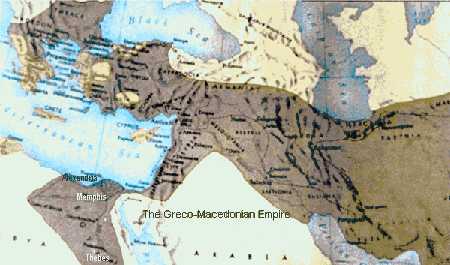

The Greek urban culture passed through three stages: the Hellenic, Hellenistic,

and Greco-Roman Ages. The Hellenic Age began with the foundation of the first

city-states (at the end of the 9th century BC) and endured until the

defeat of their confederation from the Macedonians. The Hellenistic Age endured

from the foundation of the Greco-Macedonian Empire to the defeat of its last

remnant (the Greco-Egyptian Ptolemaic Dynasty) from the Romans in 31 BC. The

Greco-Roman Age endured nearly five centuries until the nomadic Mongolian and

German tribes thwarted the Greco-Roman cultural development in another direction

at the end of the 5th century AD.

At the beginning of the Hellenic Age, the personal relationship between two

individuals and the aristocratic personal bravery and loyalty were

the pivotal center of the social (moral) thought. At the peak of the Hellenic

Age, the citizen’s relationship to the legal city-state and the idea of

the active citizenship (‘daring with deliberation’) had been the center

of cultural and political life. At the end of the Hellenic Age, the upper and

middle classes of the Greek city-states tired from the nearly century long

warfare and numerous riots. The intellectuals of both classes tried to find the

ways to reconcile their classes antagonistic interests and came up with a

synthetic moral ideology that would assist them in this task. Thus, once more,

the social scientists and priests looked back to the East (in their Aryan

heritage) trying to find answers on the critical issue – how could be balanced

the conflicting interests of the upper and middle classes. Thus, they divided

the Hindu teaching about the seasons of life and tried to dig down into them,

and thus, they created the separate doctrines that would correspond to each

separate season of life. Therefore, the principal doctrines of the Hellenistic

Age were – 1) Epicureanism, as corresponding to the student’s season of life; 2)

Stoicism, as corresponding to the householder’s season of life; 3) Skepticism –

the retiree’s season of life; and 4) Cynicism – the complete stranger’s season

of life.

1. Epicureanism

Previously the city-state had given a Greek an identity, and

only in own city he could live a fulfilled and happy life. With the coming

empire, the situation drastically changed. Although cities retained the internal

autonomy, they had lost their army and their sovereignty in the foreign affairs.

They were not any longer the sovereign and self-sufficient communities. Now the

social scientists and priests no longer assumed that the happy and fulfilled

life was tied to the affairs of the city-state. Not the active citizenship and

social responsibilities, but the freedom from emotional stress became the

highway to the fulfilled life.

Previously the city-state had given a Greek an identity, and

only in own city he could live a fulfilled and happy life. With the coming

empire, the situation drastically changed. Although cities retained the internal

autonomy, they had lost their army and their sovereignty in the foreign affairs.

They were not any longer the sovereign and self-sufficient communities. Now the

social scientists and priests no longer assumed that the happy and fulfilled

life was tied to the affairs of the city-state. Not the active citizenship and

social responsibilities, but the freedom from emotional stress became the

highway to the fulfilled life.

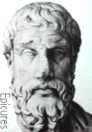

Epicures, reflecting the Greek’s changing attitude and relationship to the city

and the State, taught the moral of passive intake – as a student does

when he listens his teacher. Solon and Socrates believed that individuals attain

happy and fulfilled life through their own efforts, unaided by the gods.

Therefore, they thought that the active citizenship was a necessary prerequisite

for individual happiness, for social justice and stability. However, to

Epicures, the passivity and withdrawal from the civic duties became the main

virtue. Wise persons, said Epicures, would refrain from engaging in public

affairs, for politics could deprive them of their self-sufficiency, their

freedom to choose and to act accordingly.

On the previous stage of the social development, the starting point of moral was

the citizen’s relationship to the semi-tribal city-state. Now its point of

departure became from the relationship of an individual to the Empire-State and

the entire humanity, because now the individual’s fulfillment and happiness

depended on a larger and more complex world. Now the moralists tried to deal

with the feeling of alienation of the upper and middle classes Greeks from the

city and their attachment to the community-at-large. This Empire-State provided

them with greater material incentives, but with fewer, colder, and more

bureaucratic personal relationships.

To attain the peace of mind in such a competitive and hostile environment,

Epicures advised that the wise individuals would not pursue the social power

-- wealth or fame -- or the sensual pleasure -- love and hate, for the

pursuit would only provoke anxiety. ‘A free life cannot acquire many

possessions, because this is not easy to do without servility to mobs or

monarchs.’ The sensual pleasures have their natural limitations, and therefore,

the unpleasant after-effects (such as hangovers or heart burning) could be

avoided and happiness could be pursued with reason. Epicures advised to live

justly, for one who is unjust, burdens self with troubles. ‘But the greatest

good is prudence, for from prudence are sprung all the other virtues, and it

teaches us that it is not possible to live pleasantly without living prudently

and honorably and justly.’

People could have happy and fulfilled life when their bodies are ‘free from

pain’ and their minds ‘released from worry and fear’.

People could not be happy when they worried about dying. The dread that the gods

could interfere in human life and inflict sufferings even after death, Epicures

considered as the main cause of the individual’s anxiety. ‘Many at one moment

shun death as the greatest of evils in life. However, the wise man neither seeks

to escape life nor fears the cessation of life, for neither does life offend him

nor does the absence of life seem to be any evil.... A man cannot dispel his

fear about the most important matters if he does not know what is the nature of

the universe but suspects the truth of some mythical story. So that without

natural science it is not possible to attain our pleasures unalloyed.’ To

eliminate this main source of the human anxiety, he proposed to displace the

theory of the active gods with the Democritus’ atomic theory, which taught that

all things in the universe consist of the indivisible and colliding atoms. For

if the universe is so ordered, then there is no necessity for a divine

intervention. Therefore, even if the gods exist, they are not active and could

not influence our affairs. However, as we know it now, the atom is infinitely

divisible, and therefore, is infinite and contains a whole universe in itself;

and therefore, is God in itself. Thus, the problem of the dying anxiety persists

to these days.

In general, although Epicures discarded the active part of any adventure (daring),

he embraced the traditional middle-class insistence on prudence and moderation (deliberation).

2. Stoicism

The Hellenistic Greeks had to examine their place in a more complex and more

threatening world than the city-state was. They had to perceive a larger

community more distant from an individual than the semi-tribal city-state was,

although with greater material opportunities. Therefore, Stoicism became the

main ideology of the Hellenistic Age. Although the Stoics did not perceive

passivity as a virtue, they recognized and struggled with the problem of

alienation of an individual from a community. They tried to buttress the inner

strength of the individual in order that he could endure in the larger,

Empire-State (without the semi-tribal city-state support and security).

Moreover, these moralists wanted the individual to be active and happy, as is

appropriate for middle-aged people. By stressing the inner strength of an

individual in dealing with his misfortunes, the Stoics went deeper than the

Hindus did into the program of the individual happiness in the world with

greater uncertainties. However, this profundity came with the narrow

applicability of their doctrine, because Stoicism can be applied only to

physically active middle-aged people.

The main principle of the Stoicism may be summed up as follows – ‘all

inhabitants of this world should not live differentiated by the laws of their

separate city-states, but they should consider all men to be of one State. The

united people should have a common life and order, as a herd that feeds together

and shares the common field’.

Zeno, the founder of the Stoicism believed that the universe contained Chaos and

Order in itself. This Order he variously called as the Divine Fire, Divine

Reason, Logos, and God – in short, the universal conscious. The Chaos for

him was Nature or the universal body and its subconscious. The universal

conscious that underlies the universe and reality, permeated all things, and

accounted for their orderliness. Zeno reasoned that people were part of the

universe, and as such, they shared in the universal conscious. This universal

conscious was implanted in every human being and enabled all physically active

adults to act consciously (reasonably) and to comprehend the principles of the

universal order. Because the universal reason was common to all people, all

adult individuals were essentially (by the reasoning abilities) equal, and as

such, were brothers and sisters to each other. The individual’s reason (his

conscious) gave him his dignity and enabled him to recognize and respect the

dignity of others. To the Stoics, all people, despite their differences by

race, ethnicity, or social rank, were fellow human beings; and one law, the law

of the universe, should be applied to all of them.

Pericles reminded the Athenians about their civic duties to abide by the laws

and traditions of the city; the Stoics considered people as the citizens of the

world and emphasized the individual’s cosmopolitan duty to understand and obey

the universal laws. Socrates taught a morality of self-mastery based on reason

and knowledge and the Stoics followed him, believing that the main human quality

was the ability to reason. They also believed that the individual’s happiness

came from his conscious disciplining of his unconscious emotions. The Stoics

maintained Socrates’ conclusion that the individual, through moral perfecting

his conscious (reason), could perfect his unconscious character.

The Stoics believed that the wise man should order his life according to the

universal law, the law of Reason, which underlay the universe. Harmony between

the individual reason and the universal reason would give the individual his

inner strength to resist the sufferings (inflicted by own passion or "wrong"

reasoning that would compel other individuals to torment him). Thus, the

individual would remain undisturbed by life’s calamities through self-mastery of

the inner peace and happiness. Even if he lost his external freedom and his body

was subjected to the power of his master, his mind remained independent and

free.

The Stoics taught that, by organizing a single society, the world would be

transformed into the well-ordered commonwealth that would be based on the law of

Reason (the natural law). Plutarch asserted that Alexander was inspired by these

high ideals of the oneness of humanity and human equality before law. Because of

Alexander’s conquests of the lands between Greece and India, thousands of Greek

soldiers, bureaucrats, and merchants settled in the lands of their Indo-European

(Aryan) ancestors. Their encounters with own well-forgotten past and with new

cultures opened their minds to new possibilities and weakened their attachment

to their native cities. Now the individual’s identity was defined not by the

semi-tribal city-state, but by the empire-State. In his Morals, Plutarch

described Alexander as a social scientist in action:

"Plato wrote a book on the One Ideal

Constitution, but because of its forbidding character he could not persuade

anyone to adopt it. But Alexander established more than seventy cities among

savage tribes, sowed all Asia with Grecian [governmental forms, VS], and thus,

overcame its uncivilized and brutish manner of living. Although few of us read

Plato’s Laws, yet hundreds of thousands have made use of Alexander’s

laws... Those who were vanquished by Alexander are happier than those who

escaped his hand; for these had no one to put an end to the wretchedness of

their existence, while the victor compelled those others to lead a happy life...

Thus, Alexander’s new subjects would not have been civilized, had they not been

vanquished. Egypt would not have its Alexandria, nor Mesopotamia its Seleucia...

nor India its Bucephalia, nor the Caucasus a Greek city... for by the founding

of cities in these places savagery was extinguished; and the worse element,

gaining familiarity with the better, changed under its influence. If, then,

philosophers take the greatest pride in civilizing and rendering adaptable the

intractable and untutored elements in the human character, and if Alexander has

been shown to have changed the savage natures of countless tribes, it is with

good reason that he should be regarded as a very great philosopher."

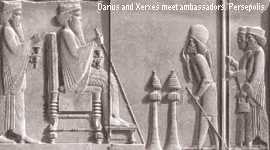

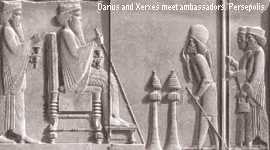

Alexander believed that all human beings were one people who

subjected to one law of reason and one form of government. He tried to implement

this ideology by taking a Persian bride and arranging the marriages for eighty

of his officers and ten thousand of his soldiers with the Persian women. For

Alexander did not follow Aristotle’s advice to treat the Greeks as if he were a

leader among friends and kindred, and other people as if he were a master among

plants and animals. Despite Aristotle’s promotion of the inductive and deductive

methods of thinking, he himself was more a scholastic-theoretician than a

systematic practitioner. When the practical Alexander encountered the Persians,

he realized that he is among kindred, although more distant than the Greeks

were. He decided that it would be cumbersome to his leadership to follow

Aristotle’s advice, because such behavior would only increase the numbers of his

battles by spawning the numerous seditions. That is why the Persians resisted

him so little that, in several years and with a small army, he could capture the

empire that had been built on blood for centuries.

Alexander believed that all human beings were one people who

subjected to one law of reason and one form of government. He tried to implement

this ideology by taking a Persian bride and arranging the marriages for eighty

of his officers and ten thousand of his soldiers with the Persian women. For

Alexander did not follow Aristotle’s advice to treat the Greeks as if he were a

leader among friends and kindred, and other people as if he were a master among

plants and animals. Despite Aristotle’s promotion of the inductive and deductive

methods of thinking, he himself was more a scholastic-theoretician than a

systematic practitioner. When the practical Alexander encountered the Persians,

he realized that he is among kindred, although more distant than the Greeks

were. He decided that it would be cumbersome to his leadership to follow

Aristotle’s advice, because such behavior would only increase the numbers of his

battles by spawning the numerous seditions. That is why the Persians resisted

him so little that, in several years and with a small army, he could capture the

empire that had been built on blood for centuries.

Alexander believed that he came as a heaven-sent governor and mediator for the

entire world. Those whom he could not persuade to unite with him, he conquered,

thus bringing together all men, uniting and mixing them into one great

melting-pot, where the men with different characters, marriages, and habits

would be equal before law. Alexander bade all people to consider his empire as

their fatherland where they should discern each other not by their

external characteristics (such as color of their clothes, eyes, hair, skin, or

by the shape of their noses or ears, or by their food and marriages), but only

by their internal values-virtues (goodness and wickedness).

After Alexander’s death, his generals divided the vast empire into three

kingdoms, the bureaucracies of which consisted of mercenaries of middle-class

Greeks and the loyal upper class Macedonians. As the trade and travel between

Greece and India expanded, and the Greek merchants and bureaucrats settled in

the lands (where a millennium ago their ancestors used to pasture the sheep and

cattle), they spread the Greek culture. They pushed the world toward the

intermingling of the different (and not so different) cultural traditions. The

Greek traditions and beliefs spread to the East, while the Indian, Persian,

Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Phoenician and other Semitic traditions and beliefs

moved into Europe. A growing cosmopolitanism replaced the localism of the

city-state. Although the majority of the officer corpus of the Macedonian armies

consisted of Greek-mercenaries, the inner-circle of the Macedonian kings

consisted of the loyal Macedonian aristocrats, and thus, the bureaucracies of

these kingdoms were molded by the hierarchical, hereditary aristocracy patterns.

The Macedonian rulers encouraged the practice of worshiping

the king as a god or as his representative on the earth. For instance, the

Egyptian priests conferred on the king of the Greco-Egyptian Dynasty the same

divine powers that were previously conferred by them onto the king of the

Persians and on the kings of all 25 previous dynasties. The Macedonian kings,

following the Alexander’s lead, founded new cities modeled after the Greek

cities. These new cities adopted the political institutions of the Hellenic

Greece, including a popular legislative Assembly and an aristocratic executive

Council. The Macedonian kings usually did not intervene into the internal city

affairs, because the executive council usually consisted of the upper class and

the assembly could not consider the issues of the foreign affairs. Hellenistic

cities, inhabited by diverse racial and ethnic groups were dominated by a

Hellenized upper class, which overcame linguistic and racial distinctions.

Koine had been a Greek dialect that was spoken throughout of the

Mediterranean world.

The Macedonian rulers encouraged the practice of worshiping

the king as a god or as his representative on the earth. For instance, the

Egyptian priests conferred on the king of the Greco-Egyptian Dynasty the same

divine powers that were previously conferred by them onto the king of the

Persians and on the kings of all 25 previous dynasties. The Macedonian kings,

following the Alexander’s lead, founded new cities modeled after the Greek

cities. These new cities adopted the political institutions of the Hellenic

Greece, including a popular legislative Assembly and an aristocratic executive

Council. The Macedonian kings usually did not intervene into the internal city

affairs, because the executive council usually consisted of the upper class and

the assembly could not consider the issues of the foreign affairs. Hellenistic

cities, inhabited by diverse racial and ethnic groups were dominated by a

Hellenized upper class, which overcame linguistic and racial distinctions.

Koine had been a Greek dialect that was spoken throughout of the

Mediterranean world.

Hellenistic cities engaged in economic activities

on a larger scale than the Greek city-states. The market economy developed in

the integrated area of Greece and the Near East. Business methods became more

refined. The increased movement of peoples led to the adoption of common

currency standards. International trade became easier through the improvements

in navigation techniques, better port facilities, and a decrease of barter and

an increase in the monetary and banking economy. The wealth of the upper and

middle classes surpassed the wealth of the Periclean Athenians.

Hellenistic cities engaged in economic activities

on a larger scale than the Greek city-states. The market economy developed in

the integrated area of Greece and the Near East. Business methods became more

refined. The increased movement of peoples led to the adoption of common

currency standards. International trade became easier through the improvements

in navigation techniques, better port facilities, and a decrease of barter and

an increase in the monetary and banking economy. The wealth of the upper and

middle classes surpassed the wealth of the Periclean Athenians.

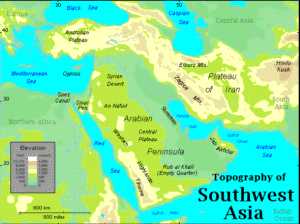

The greatest city of the Hellenistic Age was Alexandria, founded by Alexander

the Great in Egypt. Strategically located at the mouth of the Nile, Alexandria

was an unrivaled commercial and cultural center of that time; goods from the

Mediterranean world, east Africa, Arabia, Persia, and India circulated in its

marketplaces. This cosmopolitan center, with its voluminous library, attracted

all kinds of scientists, artists, and poets. Alexandrian physicians advanced

medical skills and improved surgical instruments and techniques of operation. By

dissecting bodies, they added to the anatomical knowledge of the time. Their

advanced knowledge of human anatomy and physiology was not significantly

improved for nearly the two next millennia.

Mathematical and astronomical knowledge was also developing faster than it had

been developing in the Hellenic Athens. Eighteen centuries before Copernicus,

the Alexandrian astronomer Aristarchus asserted that the earth was a planet that

revolved around the sun, and that the stars were situated at great distances

from the earth. The Alexandrian mathematician Euclid creatively deducted

hundreds of geometrical theorems that were proven based on the deductive method

alone and were a profound witness to the power of the human mind. Archimedes, a

Syracusan who studied mathematics and physics at Alexandria and later became

known as an ingenious inventor of the war engines and other mechanical devices,

established a new branch of physics (hydrostatics) that studies the pressure of

liquids at rest. The Alexandrian geographer Eratosthenes sought a scientific

explanation for this enlarged Hellenistic world. He divided the earth into its

climatic zones and asserted that the oceans are joined. He also accurately

measured the circumference of the earth.

The makeup of the Hellenistic armies also reflected this

cosmopolitan spirit. The serving-men came from the lands that stretched from the

banks of the Indus River on the East to the banks of the Guadalquivir River on

the West, from the Danube in the North to the Nile in the South. In the

ex-Phoenician, ex-Egyptian, and ex-Syrian cities, a middle-class emerged, the

members of which spoke fluent Greek, wore and used Greek-style clothes, homes,

and furniture, and adopted the Greek customs. Sculptures and other artifacts of

that era show the influence of many lands and peoples. The historians were

accustomed to writing not only local chronicles, but also first-class world

histories. The Hellenistic social scientists demonstrated a fascination with the

traditions and beliefs of the Hindus, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, Jews,

Babylonians, Egyptians; and they soon translated the Scriptures of these

ideologies into Greek. Actually, the Greeks creatively developed Stoicism from

Hinduism and Buddhism, as they previously developed the Golden Ratio from the

Egyptian Canon of Proportions.

The makeup of the Hellenistic armies also reflected this

cosmopolitan spirit. The serving-men came from the lands that stretched from the

banks of the Indus River on the East to the banks of the Guadalquivir River on

the West, from the Danube in the North to the Nile in the South. In the

ex-Phoenician, ex-Egyptian, and ex-Syrian cities, a middle-class emerged, the

members of which spoke fluent Greek, wore and used Greek-style clothes, homes,

and furniture, and adopted the Greek customs. Sculptures and other artifacts of

that era show the influence of many lands and peoples. The historians were

accustomed to writing not only local chronicles, but also first-class world

histories. The Hellenistic social scientists demonstrated a fascination with the

traditions and beliefs of the Hindus, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, Jews,

Babylonians, Egyptians; and they soon translated the Scriptures of these

ideologies into Greek. Actually, the Greeks creatively developed Stoicism from

Hinduism and Buddhism, as they previously developed the Golden Ratio from the

Egyptian Canon of Proportions.

In the representation of the human figure, the Egyptian painters and sculptors

were guided by so-called canons, which changed slightly during two

millennia of the Old and the New Kingdoms. These canons were the rules of

proportions that set out the ideal measurements for depicting human figures and

the ideal relationships between their parts. The Egyptian artists constructed a

grid in which each square measured one half of a unit. For instance, the

distance from the bottom of the hair or wig to the shoulder was a unit, from the

shoulder to the bottom of the tunic – five units, and so forth. The main purpose

of this ideal system was to ease the construction of a generally recognizable

royal image.

On the other hand, the Greeks thought that not only the members of royal

families actively participated in history but also the talented members of the

upper and middle classes (the appointed leaders, orators, scientists, athletes,

actors, etc.). Therefore, the Greeks created own canons, which were based on the

Golden Ratio. The Greeks thought that any form (including the

human figure) is most aesthetically pleasing when it is constructed in accord

with the Golden Ratio.

Through the process of systematizing the Greeks’ spiritual and material values,

we can discern their evolutionary process. This evolution went from the

monarchical city-state through the city-state with the aristocratic republic, in

which the upper class was dominant through the military bureaucracy. The

evolution continued through the city-state with the commoners’ republic, in

which the middle class was dominant through the civil bureaucracy. The evolution

continued through the republican empire to the monarchical empire, with the

following dissolution of the Greek culture in the larger, Greco-Roman culture.

The spiritual and material values of the Greeks

do not come down to us merely by way of a few artifacts of marble or bronze.

They are still alive in us as a synthetic idea – the idea of emotional, yet

systematically rational common man, who should be the measure of all things. The

Greeks’ spiritual and material culture is the actual record of their history.

Through the changes in their material culture (architecture, sculpture,

painting, and other artifacts), we can scan the years that were missing from the

records of their spiritual culture. Thus, we can see the ever-evolving

continuity and duration – the birth of Greek culture from the smaller two, its

flowering, its decline and its rebirth in a larger culture.

The spiritual and material values of the Greeks

do not come down to us merely by way of a few artifacts of marble or bronze.

They are still alive in us as a synthetic idea – the idea of emotional, yet

systematically rational common man, who should be the measure of all things. The

Greeks’ spiritual and material culture is the actual record of their history.

Through the changes in their material culture (architecture, sculpture,

painting, and other artifacts), we can scan the years that were missing from the

records of their spiritual culture. Thus, we can see the ever-evolving

continuity and duration – the birth of Greek culture from the smaller two, its

flowering, its decline and its rebirth in a larger culture.

The earliest period in which the Greeks made life-size stone sculpture is called

the Archaic Period. It left a rich and vivid record of how the Greeks idealized

the human form. The figures are massive, crude, and excessively abstract. They

are not meant to portrait the common men, but rather, they stand for the idea of

an immortal hero, a semi-god. This figure expresses the highest point of the

inductive reasoning, which arrived at the idea of ever evolving, yet changeless

eternity – Father-God, Mother Nature, or both.

The sculptures retain the rigid and blocky form of the stone from which they

were cut. The use of this technique suggests that the sculptors were under the

impression of the idea of immortal and omnipresent power. The sculptures stand

poised and serene, emanating the feeling of awe and inferiority. For those early

Greek artists moving matter and its space and time meant little, as for their

teachers – the Egyptian artists, because space and time (as the indispensable

characteristics of the spiritual and physical reality) were not a part of their

consciousness. They only felt it on the subconscious level, because the

consciousness includes not only the inductive reasoning, but also the deductive

one and their systematization (synthesis).

The early Greek artists did not think deductively, moreover, systematically,

about themselves, their society, and its environment. Thus, their sculptures

were not a thorough reflection of the contemporary reality with its real forms,

but rather those sculptures (with their clenched fists and the arms pressed

against the side were to stand) were the representation of the upper class

monarchical ideology. The latter was created with the intent to repress and

subjugate the commoners, spiritually and materially. That is why the facial

expression of the early Greek sculptures (the so-called Archaic smile) was

intended to extract from a viewer the feeling of awe, fear, and inferiority. The

sculptures represented the abstract and universal, not the casual and

particular. Individualism was carefully excluded because, for the earliest,

semi-nomadic, semi-tribal Greeks, their gods symbolized the abstract, inductive,

and universal powers.

Centuries passed. The Greeks gradually developed their spiritual and material

culture. They became more sophisticated. The structure of their society, of

their city-state, became more discernible and stabilized. They developed their

agriculture and industry. Their middle class of merchants, farmers, and artisans

developed own ideology and became dominant (through the civil bureaucracy) in

the society.

The Greeks respected the old gods, but now had a

higher regard for the common man and his material and spiritual life. Athletes

and philosophers became more respectable than the war heroes and semi-gods. The

images of the former were captured on vases, in bronze, and in stone. Their

models were now the common men, not the idealized universal powers. That can be

seen in the sculpture of the Charioteer, from the early 5th century

BC. The Charioteer is not as simplified and geometric as the earlier Archaic

figures. However, his robe hangs straight and still. His body is stiff and

erect. We do not see the drama and action of the event. Rather, the sculptor has

given us the idealized symbol of the victor in a game. Although the features of

the face are serene and timeless, yet now there are touches of realism in the

youthful sideburns and the unshaven face. This subtleties and details of the

weekday human life was totally absent in the art of the previous century.

The Greeks respected the old gods, but now had a

higher regard for the common man and his material and spiritual life. Athletes

and philosophers became more respectable than the war heroes and semi-gods. The

images of the former were captured on vases, in bronze, and in stone. Their

models were now the common men, not the idealized universal powers. That can be

seen in the sculpture of the Charioteer, from the early 5th century

BC. The Charioteer is not as simplified and geometric as the earlier Archaic

figures. However, his robe hangs straight and still. His body is stiff and

erect. We do not see the drama and action of the event. Rather, the sculptor has

given us the idealized symbol of the victor in a game. Although the features of

the face are serene and timeless, yet now there are touches of realism in the

youthful sideburns and the unshaven face. This subtleties and details of the

weekday human life was totally absent in the art of the previous century.

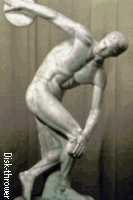

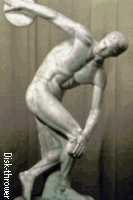

A few decades later, the Disc-thrower would vividly indicate the change that

took place in the Greek’s outlook. Now the arms reach out into space. The tense

body is twisted, crouches slightly, and poised in anticipation of the throw. He

is a man about to be in swift motion; and time and space are indispensable

characteristics of the moving matter. Thus, the Greeks moved from their Archaic

2D world of the eternal and the changeless and entered the 3D world of moving

matter.

Thus, the Greek history shows us the change to an age not

only of supermen, but of the common men also. First, the archaic warrior (with

his virtue of manhood) marches into battle like mechanical robot. The face of

that old hero tells you – ‘keep smiling never matter what’. His body is rigid

and unyielding. Later, by the mid-5th century BC, the past stiff

angularity is no longer discernible. The horsemen from the friezes of the

Parthenon symbolized a new age, relaxed and confident – the Periclean, the

Middle-class Age of Greece, with the new virtue of goodness – daring with

deliberation. Thus, the new hero (who was immortalized through the Parthenon’s

horseman) is soft, fleshy, and reflect the natural movement. However, both

sculptures reflect the humane dignity and self-restraint, so much admired by

both major classes of the Greeks.

Thus, the Greek history shows us the change to an age not

only of supermen, but of the common men also. First, the archaic warrior (with

his virtue of manhood) marches into battle like mechanical robot. The face of

that old hero tells you – ‘keep smiling never matter what’. His body is rigid

and unyielding. Later, by the mid-5th century BC, the past stiff

angularity is no longer discernible. The horsemen from the friezes of the

Parthenon symbolized a new age, relaxed and confident – the Periclean, the

Middle-class Age of Greece, with the new virtue of goodness – daring with

deliberation. Thus, the new hero (who was immortalized through the Parthenon’s

horseman) is soft, fleshy, and reflect the natural movement. However, both

sculptures reflect the humane dignity and self-restraint, so much admired by

both major classes of the Greeks.

The inductive rhythm of the beginning of Greek art was later combined in the

Periclean Age with the human individualistic characteristics, which had been

growing in importance as the Greek culture mellowed. The middle-class systematic

art balanced inductive-deductive geometry of the upper-class cold superman with

the warm, emotional, and moving nature of the common man. It was a brief

historical balance that came between two wars, eighty years apart – the Ionian

Greeks’ victory over the Persians and the Ionian Greeks’ defeat from the Dorian

Greeks.

The systematic rhythm and naturalness of the

Spearbearer and the Parthenon friezes soon slipped into the upper class

pretentious pose, with smooth muscles that flows beneath the soft skin of the 4th

century statue of Hermes, carrying the infant Dionysus. The body of Hermes sways

into a relaxed S-curve. The marble has been polished in such a degree as to

simulate the soft warmth of feminine skin. Thus, the sculptor of the Hermes

exceeded the systematic naturalism and restrained idealism of the previous

generation of artists. By the end of the 4th century, in the

aftermath of the conquests of Alexander the Great, the new and excessively

refined Greek culture moved into the Near East and northern Africa. The days of

the middle class dominated Ionian Greeks were numbered, and the Greco-Macedonian

Monarchical Empire soon replaced the remnants of their Republican Empire.

The systematic rhythm and naturalness of the

Spearbearer and the Parthenon friezes soon slipped into the upper class

pretentious pose, with smooth muscles that flows beneath the soft skin of the 4th

century statue of Hermes, carrying the infant Dionysus. The body of Hermes sways

into a relaxed S-curve. The marble has been polished in such a degree as to

simulate the soft warmth of feminine skin. Thus, the sculptor of the Hermes

exceeded the systematic naturalism and restrained idealism of the previous

generation of artists. By the end of the 4th century, in the

aftermath of the conquests of Alexander the Great, the new and excessively

refined Greek culture moved into the Near East and northern Africa. The days of

the middle class dominated Ionian Greeks were numbered, and the Greco-Macedonian

Monarchical Empire soon replaced the remnants of their Republican Empire.

The difference between the middle class dominated Greeks and the following upper

class dominated Hellenistic Greeks can be demonstrated by a comparison of two

places, which represent the artistic crux of the respective ages. These two

places are – the Acropolis of Athens and the Acropolis of Pergamon, in Asia

Minor. As can be seen in the reconstruction, Pergamon had a magnificent

Acropolis, which was built during the 2nd century BC.

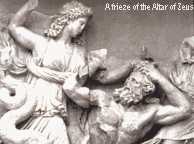

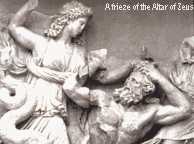

Atop of the Pergamon’s Acropolis was built the Great Altar

to Zeus, which reflected the age of the monarchical empire in the same way as

the Parthenon reflected the age of the middle class dominated society. The

development of Greek culture in broad instead of in deep, extensively instead of

being intensive, had been reflected in a strong sense of widening space. The

Great Altar of Zeus seems invited the worshipper to enter. Its huge staircase

was its central feature, the steps of which was constructed that way with intent

to extract from the worshipper a feeling of expanding universe, by inviting the

worshipper to move upward, further and further. Atop of the staircase stands a

row of columns, which seem from below as the continuation of the steps, which

invite the worshipper to step down into the wide cosmos.

Atop of the Pergamon’s Acropolis was built the Great Altar

to Zeus, which reflected the age of the monarchical empire in the same way as

the Parthenon reflected the age of the middle class dominated society. The

development of Greek culture in broad instead of in deep, extensively instead of

being intensive, had been reflected in a strong sense of widening space. The

Great Altar of Zeus seems invited the worshipper to enter. Its huge staircase

was its central feature, the steps of which was constructed that way with intent

to extract from the worshipper a feeling of expanding universe, by inviting the

worshipper to move upward, further and further. Atop of the staircase stands a

row of columns, which seem from below as the continuation of the steps, which

invite the worshipper to step down into the wide cosmos.

On the other hand, the dominant structural motif of the Parthenon was the rows

of columns, which enclosed one in the cozy temple, where one felt oneself

comfortable, as in own home. The sculptural decoration on the Parthenon was

placed behind and above the Doric columns. The intent was to subordinate the

sculptures to the columns and the latter to the whole structure, thus making the

Parthenon synthetic and comfortable. The Parthenon’s frieze is shallow in

carving, restrained, and its rhythm changes unchanging, like its columns.

In contrast, the Altar of Zeus stresses the

sculptural frieze, which was now at the bottom of the staircase, easy accessible

to a viewer. Moreover, the sculpture of frieze is now deeply carved. The theme

of the sculpture is the War of the Giants and the Gods. Through the theme of the

sculpture and its deep carving, the sculptors tried to instigate energy of the

climbers, who would stumble over the first step. The rhythm of the sculptures is

rugged and not organic. These sculptures convey the feeling of their agitated

and restless motion into a wide cosmos. Serenity and humane dignity of the

Parthenon’s figures no longer appealed to the hearts and minds of the

Hellenistic Greeks, who now prefer the muscular and emotional figures. The love

of harmony and balance, which was in favor in the middle class dominated

society, now was replaced for an extremely emotional outlook, which was

reflected in the hysterical and twisted bodies, whose realism and individuality

was exaggerated for the greater shock appeal.

In contrast, the Altar of Zeus stresses the

sculptural frieze, which was now at the bottom of the staircase, easy accessible

to a viewer. Moreover, the sculpture of frieze is now deeply carved. The theme

of the sculpture is the War of the Giants and the Gods. Through the theme of the

sculpture and its deep carving, the sculptors tried to instigate energy of the

climbers, who would stumble over the first step. The rhythm of the sculptures is

rugged and not organic. These sculptures convey the feeling of their agitated

and restless motion into a wide cosmos. Serenity and humane dignity of the

Parthenon’s figures no longer appealed to the hearts and minds of the

Hellenistic Greeks, who now prefer the muscular and emotional figures. The love

of harmony and balance, which was in favor in the middle class dominated

society, now was replaced for an extremely emotional outlook, which was

reflected in the hysterical and twisted bodies, whose realism and individuality

was exaggerated for the greater shock appeal.

The Greek culture was dominant in the Mediterranean region from the mid-Hellenic

to the mid-Hellenistic periods. Nevertheless, it was exposed to diverse

languages, customs, and ideologies. Correspondingly, it was enriched by the

cross-fertilization, particularly, by Buddhism.

a. The Points of Connection of the Stoicism and the Knowledgeable One’s

Ideology (Buddhism)

Buddha (c.563-483 BC) was born in Nepal. Siddhartha was his

given name, Gautama – his surname, and Sakyas – the name of his tribe. His

father was a chieftain in a small horticultural confederation. He was brought up

in luxury and had been exceptionally handsome. At sixteen, he married a

neighboring princess, Yasodhara, who bore him a son – Rahula.

Buddha (c.563-483 BC) was born in Nepal. Siddhartha was his

given name, Gautama – his surname, and Sakyas – the name of his tribe. His

father was a chieftain in a small horticultural confederation. He was brought up

in luxury and had been exceptionally handsome. At sixteen, he married a

neighboring princess, Yasodhara, who bore him a son – Rahula.

Buddha appeared to have everything: wealth, handsome looks, family, and was

destined for the social power. Despite all this worldly success, Buddha yearned

for spirituality. When he was born, his father summoned fortunetellers to find

out what the future held for his heir. The fortunetellers agreed that this was

not a usual child; they also agreed that if he remained with this world – he

would become the greatest conqueror of the world, the India’s unificator and

benefactor, the Universal King. On the other hand, if he would not be the world

conqueror, then he would be the World Redeemer.

Facing with these options, his father bent for the first option and decided to

surround Buddha with all the sensual pleasures, thinking that they would attach

Buddha to this world. He surrounded Buddha with dancing girls and shielded him

from the sick, decrepit, and ugly individuals – even when Buddha rode, the

runners cleared the road before him from such persons. However, one day, Buddha

encountered with a decrepit, broken-toothed, gray-haired man who was crooked and

bent bodily, leaning on a staff, and trembling. Thus, Buddha learned the bitter

fact of the old age. Then he encountered with a sick person, lying by the

roadside; and after that he encountered with a corpse. Then he encountered with

a shaven-head monk, in the ochre robe, with a bowl, and learned about the people

who withdrew from this world. Thus, he concluded that the body is temporal and

subject to destruction. He became anxious about death and asked himself a

question – if life transfers into death, and then, is there somewhere the realm

of life in which there is neither age nor death?

This anxiety of dying became his mania-nervosa until he found the source of it

and became Buddha, because Buddha, from Sanskrit, means ‘to wake up’ and ‘to

know’; thus, he became the ‘Awakened One’ or ‘Knowledgeable One’. The

Knowledgeable One becomes such from a moment when a person shakes off the

doze of ordinary awareness from himself and wakes up for the happy life that is

without the anxiety of dying.

Once the Knowledgeable One-to-be had perceived the inevitability of the bodily

pain and its decay, the sensual pleasures lost their charm. The singsong of the

dancing girls, the rhythmic tune of flutes and cymbals, the sumptuous feasts and

processions only mocked his infected mind. He was determined to quit the

destructive snare of his home and to follow the way of a truth-seeker. He said

goodbye to his wife and son and went to a forest. When he reached the edge, he

changed his clothes, shaved his head, and plunged into the forest in search of

the knowledge.

During the following six years, he concentrated toward this goal and his search

was not easy. His search moved through three distinctive stages. The first

stage was to seek out two of the most prominent Hindu-masters of the day and

pick their wisdom of this vast tradition. He learned a great deal about the

psychosomatic discipline (raja yoga) and the Hindu ideology. In fact,

the Hindus claim that the Knowledgeable One was one of their own; they hold that

he was a dissenter in order to reform Hinduism, and that his agreements were

more important than his dissent. However it could be, in due time, he decided

that he had learned all that Hinduism could teach him.

The second stage came when the Knowledgeable One-to-be joined a band of

ascetics, in order to try their way. He thought that his sensual body powerfully

interfered in the work of his mind. Therefore, he should subdue it with

austerity. Sometimes he grew so weak that he fainted; and if his companions had

not been feeding him some warm rice, he could easily be dead. Thus, he learned

the futility of asceticism. This experience did not bring him the knowledge, but

the negative results could also teach something. Thus, he realized his first

principle – the Middle Way between the two extremes of asceticism and

indulgence. He embraced the idea of the rationed life – the body is given what

it needs for functioning properly, but no more.

In the final stage of his quest, the Knowledgeable

One-to-be devoted himself to a combination of rigorous thought and mystic

concentration along the lines of the psychosomatic discipline. One evening he

felt that a breakthrough was near and he sat under a tree and vowed not to arise

until he gets the knowledge. On the first night of the to-be Knowledgeable One’s

temptations, the Evil One rushed to this tree trying to disrupt his

concentration by torturing him through his desires – parading three voluptuous

women with their retinues. When the Knowledgeable One-to-be did not switch his

concentration, the Evil One masked under the Death and tempted him with

hurricanes, torrential rains, and showers of flaming rocks. However, the

Knowledgeable One-to-be had so emptied himself of his selfishness that the

Devil’s weapons found no target to strike and turned into the flower petals. The

desperate Devil tried his last weapon – he challenged the Knowledgeable

One-to-be on the ground of his right to know life and death. However, the

Knowledgeable One-to-be touched the earth with his right fingertip and it

responded with an earthquake and the Devil’s army fled in rout. Then his

meditation deepened and his mind pierced at last the bubble of the universe and

he found the Gate of the Infinite Bliss. Thus, the Knowledgeable One-to-be had

transformed into the Knowledgeable One. The bliss of this experience kept him

seated under the tree for seven days; then another wave of bliss kept him

riveted to this spot for forty-two more days.

In the final stage of his quest, the Knowledgeable

One-to-be devoted himself to a combination of rigorous thought and mystic

concentration along the lines of the psychosomatic discipline. One evening he

felt that a breakthrough was near and he sat under a tree and vowed not to arise

until he gets the knowledge. On the first night of the to-be Knowledgeable One’s

temptations, the Evil One rushed to this tree trying to disrupt his

concentration by torturing him through his desires – parading three voluptuous

women with their retinues. When the Knowledgeable One-to-be did not switch his

concentration, the Evil One masked under the Death and tempted him with

hurricanes, torrential rains, and showers of flaming rocks. However, the

Knowledgeable One-to-be had so emptied himself of his selfishness that the

Devil’s weapons found no target to strike and turned into the flower petals. The

desperate Devil tried his last weapon – he challenged the Knowledgeable

One-to-be on the ground of his right to know life and death. However, the

Knowledgeable One-to-be touched the earth with his right fingertip and it

responded with an earthquake and the Devil’s army fled in rout. Then his

meditation deepened and his mind pierced at last the bubble of the universe and

he found the Gate of the Infinite Bliss. Thus, the Knowledgeable One-to-be had

transformed into the Knowledgeable One. The bliss of this experience kept him

seated under the tree for seven days; then another wave of bliss kept him

riveted to this spot for forty-two more days.

Then the Devil tempted him the last time, appealing to his reason. The Devil did

not argue the burden of re-entering into this world with its banalities; he dug

deeper. Who could be expected to understand the truth as profound as that which

the Knowledgeable One had seized and held? How could the speech-defying

revelation be translated into words, or the visions, which scatter definitions,

be caged into a language? How one can show himself that what will only be found

by him, or how one can teach self about what will only be learned by him? Why

bother yourself to play the idiot before an ignorant audience? Why not wash

one’s hands, say goodbye to own body, and slip at once into the Nirvana?

The Knowledgeable One contemplated these questions for nearly a day and then

answered, "There will be some, which will understand", and the Devil vanished

from his sight forever.

Then, for nearly a half of a century, the Knowledgeable One trampled the dusty

roads of India until his hair became white and step infirm, preaching the

ego-scattering, life-redeeming message. He founded an order of monks, challenged

the staled Hindu priests, and accepted their bewilderment and resentment. In

addition to training monks and supervising the affairs of his order, he

maintained the public preaching and private counseling, encouraging the

faithful, and comforting the distressed. The Knowledgeable One withdrew from

society for six years, and then returned into it for forty-five more years.

Following this pattern and trying to maintain his busy schedule, the

Knowledgeable One devoted nine months of a year to this world and, for the rainy

three months, he retreated to contemplate with his monks. His daily pattern was

molded in the same manner – three times a day he withdrew from the public for

meditation.

At the age of 80 and after 45 years of an arduous ministry, the Knowledgeable

One died from dysentery after eating a meal of the dried pork in the home of a

smith. While dying, he informed the smith that of all the meals he had eaten

during his long life, only two he had blessed. One of those meals gave him the

strength to reach the knowledge under his tree and the other was opening to him

the final Gate of the Infinite Bliss (Nirvana) right now.

The most striking characteristics of his personality were a combination of a

cool head and a warm heart, which shielded him from sentimentality and

indifference. His every problem, he dissected into its components, thus that

they could be reassembled in logical order, according to their meaning and

assumptions. He was a master of dialogue and dialectic. His character was

balanced with tenderness and infinite compassion. The hollow distinctions of

class and caste meant so little to him that he often appeared not to even have

noticed them. He respected all persons with whom he encountered; this attitude

stemmed from the fact that all of them were fellow human beings. He refuted all

attempts of his disciples, during his lifetime, to turn him into a god. At one

annual assembly, he asked his disciples whether in word or in deed they had

found any fault in him. When a flatterer exclaimed, "Such faith have I, Lord,

that methinks there never was nor will be nor is now any other greater or wiser

than the Blessed One", and the Knowledgeable One admonished him:

"Of course, Sariputta, you have known all

the Knowledgeable Ones of the past. No, Lord. Well then, you know those of the

future? No, Lord. Then at least you know me and can penetrate my mind

thoroughly? Not even that, Lord. Then why, Sariputta, are your words so grand

and bold?"

He did not conceal his temptations and weaknesses – he showed how difficult it

was to him to attain the knowledge and how he remains fallible. He confessed

that if he had had another so powerful drive as the sexual one, he would never

have achieved the knowledge. He admitted that the months, when he was first

alone in the forest, had brought him to the brink of mortal terror. "As I

tarried there, a deer came by, a bird caused a twig to fall, and the wind set

all the leaves whispering; and I thought, ‘Now it is coming – that fear and

terror of death’."

The entire life of the Knowledgeable One was saturated with the conviction that

he had to perform a cosmic mission. Immediately after he had had the knowledge

of life and death, his soul felt the rusty and dimmed souls of humanity that

were crashed and desperately in need of help and guidance. He had no choice but

to agree with his followers that he had been born into the world for the

advantage, the good, and the happiness of the many.

Moving from the Knowledgeable One to the religious ideology of Knowledge

(Buddhism), we must remember that it had grown from Hinduism. Unlike Hinduism,

which slowly developed from the ancient Aryan tradition through minutest

cultural accretion, the ideology of Knowledge appeared, so to speak, overnight,

and it appeared fully formed. In general, it was an ideology of reaction against

the perversions of the Hindu priests – the Indian version of Protestantism. To

understand the teachings of the Knowledgeable One, first we must understand the

general development of any ideology, either religious or political.

Six features of any ideology appear so regularly as if their seeds are in human

nature. The first one of these is authority. If we lay aside the

divine authority and approach scientifically the matter at hand, then we will

see that any ideology represents the interests of the social classes or factions

(special interest groups). An ideology is based on reasoning, and therefore, the

talented individuals, who could represent the particular interests and capture

the attention of the majority of the people, would capture the brunt of the

social prestige. They would influence governmental decisions and their advice

would be sought and generally followed. If the ideology of such talented

individuals would be institutionalized (organized as a bureaucratic body), then

these individuals would represent either political or religious authority.

The second feature of any ideology is the

ritualistic one. As the anthropologists tell us, the ancient people first

devised body language and danced out their ideology before they thought

it out. Any ideology arises out of the collective expression of joy or grief.

When I would lose a friend or when I would win millions of dollars, I would wish

not only to be with people but also to interact with them and interact in such a

way that would relieve me from my isolation. Many animal species act in such a

manner. A bumblebee would dance before her partners, showing them the way to a

rich supply of food. The families of gibbons would welcome the rising sun by

singing in unison.

The second feature of any ideology is the

ritualistic one. As the anthropologists tell us, the ancient people first

devised body language and danced out their ideology before they thought

it out. Any ideology arises out of the collective expression of joy or grief.

When I would lose a friend or when I would win millions of dollars, I would wish

not only to be with people but also to interact with them and interact in such a

way that would relieve me from my isolation. Many animal species act in such a

manner. A bumblebee would dance before her partners, showing them the way to a

rich supply of food. The families of gibbons would welcome the rising sun by

singing in unison.

An ideology usually begins from a ritual, but soon the explanations are

required; thus, the third feature of any ideology – the reason and

speculation or social conscious – appears on the stage. What is

the life, what is the death, and where do we go? People wish-to-know their

limitations.

The fourth feature of any ideology is its tradition. In a society,

it is rather a tradition than reason and speculation that preserves what past

generations have learned and transferred to the present as the pattern of an

action. Therefore, a tradition is a social instinct or

subconscious.

The fifth feature of any ideology is its mystic area, where it

tries to measure immeasurable. An ideology is a theory that is based on a system

of the axioms or beliefs. These axioms or beliefs are taken as

obvious and are very difficult to prove or disprove and usually a tradition

sustains them (like the tradition that had supported the axiom of the sun, which

revolves around the earth). An ideology must have something unknown because an

ideology always tries to explain something total (like the Universe, Nature,

God, or Communism) through the point of view of its parts (the human beings are

parts of the Universe...). The whole is greater than its part; and therefore,

the part will always have some vague knowledge about some other parts of

the whole. Therefore, any ideology would have some unknown and mystic

area, which can accommodate the imagination of its believers. However, it

should wake up the believers’ curiosity, not hinder or suppress it. This

vague knowledge must be constantly scrutinized, and the reason should not be

hiding behind the supernatural things.

The sixth feature of any ideology is faith or hope – for

what is faith if not hope, since it is the belief that the Nature, God, Power,

Justice, or Truth will eventually be on our side.

Each of these features – the authority, rituals (or body language), reason (or

social conscious), tradition (or social subconscious), vague knowledge (or

mysticism), and faith (or hope) – contributes in some degree to an ideology.

However, these features can also impede the work of an ideology. Thus, the

Knowledgeable One saw all six features impeding Hinduism.

The Hindu authority (its priests) had become hereditary and

exploitative, because they were hiding the religious secrets from the lower

classes, and because they charged excessively for their ministry to the lower

classes. The Hindu rituals, its body language, had become the mechanical devices

for evoking miracles (like the Babylonian abracadabra). The Hindu reasoning (its

social conscious) had lost its experiential base (its inductive method), and

made a stress on the deductive method of thinking, thus degenerating into the

scholastic and meaningless hair-splitting. The Hindu tradition (its social

subconscious) had turned stale, because the priests insisted on the

implementation of Sanskrit (an ancient Aryan language), which was no longer used

by the masses (like, later, Latin was used in Luther’s Germany). The Hindu

priests have considered the vague knowledge (the Hindu mysticism), as the

fantastic tricks that were necessary to maintain their social power; therefore,

the priests took all precautions that this vague knowledge would not be

clarified.

Thus, the priests, who at the beginning of the Hinduism were developing this

ideology and were the progressive leaders, now had the decelerating impact on

Hinduism and became retrogrades and a selfish caste.

Finally, the Hindu priests mistreated the faith (hope), because

they undercut the individual’s responsibilities for own deeds by substituting

the active faith (hope) with the passive faith (fatalism).

When the Knowledgeable One came onto this corrupt and degenerated Hinduism, he

determined to clear and clarify it, and to inhale a new life into it.

Thereafter, the Knowledgeable One preached an ideology that: shuns the

authority, rituals, traditions, and mysticism; and promoted the reason

and hope.

1. He preached an ideology that shuns of the authority, because, on the

one hand, he wanted-to-break the priests’ monopoly on the Hindu ideology and to

make it accessible to the masses. On the other hand, he wanted-to-challenge each

individual of the lower classes not rely passively on the priests, but search

actively own ideology. "If the teachings, when followed out and put in practice,

conduce to loss and suffering – then reject them." E. A. Burtt, The Teachings

of the Compassionate Buddha, 32.

2. He preached an ideology that shuns the rites and rituals. He

considered the Hindu rites as irrelevant to the labor of the ego-reduction. He

argued that they were worse than irrelevant because they chained the human soul.

Therefore, he resisted instituting own rituals.

3. He preached an ideology that shuns of the tradition. "Do not accept

what you hear by report, do not accept tradition, do not accept a statement

because it is found in our books, nor because it is in accord with your belief,

nor because it is the saying of your teacher. Be lamps onto yourselves. Those

who, either now or after I am dead, shall rely upon themselves only and not look

for assistance to anyone beside themselves, it is they who shall reach the

topmost height." Ibid.49.

4. He preached an ideology that shuns the supernatural things, such as

miracles and fortune telling. He condemned all kinds of mystification as low

arts. "By this you shall know that a man is not my disciple – that he tries to

work a miracle." He considered all appeals to the supernatural as the attempt to

cheat making shortcuts and simplistic solutions that divert an individual from

the hard labor of the very self-advance.

5. He preached an ideology that promoted reason and speculation. "It is

not on the view that the world is eternal, that it is final, that body and soul

are distinct, or that the Knowledgeable One exists after death, that a spiritual

life depends. Whether these views or their opposites are held, there is still

rebirth, there is old age, there is death, and grief, lamentation, suffering,

sorrow, and despair.... I have not spoken to these views because they do not

conduce to absence of passion, or to tranquillity and the Infinite Bliss

(Nirvana). And what have I explained? Misbalance have I explained, the cause of

misbalance, the destruction of misbalance, and the way that leads to the

destruction of misbalance have I explained. For this is useful." E. J. Thomas,

The Early Buddhist Scriptures, 64.

6. He preached an ideology that promoted intense self-searching, because many

people had accepted the circle of birth and rebirth as inevitable and fatal. He

considered it as the self-conviction to a nightmare of eternal hard labor. He

considered ridiculous the notion that only the priests could attain the

knowledge of life and death. He told his followers, that ‘whatever their caste

is, they can achieve the Bliss Infinity in this very lifetime’. "The

Knowledgeable One only point the way. Work out your salvation with diligence."

C. Humphreys, Buddhism, 120.

1)The Four Truths of Life

The first formal discourse of the Knowledgeable One, after his six-year quest

and awakening, was a declaration of his main discoveries, his four convictions

about life, which are the axioms of his system.

The First Truth is that life is misbalance

(dukkha). The word ‘dukkha’ was used in Pali to refer to the axle of a wheel

that was off-center or to the bone that had slipped from its socket. The exact

meaning of the First Truth is – Life is the result of a dislocation. Something

has gone wrong in the universe or in a body and it is out of joint. If its pivot

is not adjusted, is not true, and its movement is not free, then friction or

interpersonal conflict is excessive and its movement is impede, and it hurts.

The Knowledgeable One pinpointed six moments when the life’s misbalance becomes

apparent. Despite their physical, mental, or social differences, all human

beings experience six fears. These fears are – the trauma of birth, the fear of

sickness, the fear of aging, the fear of death, the fear of living among the

hateful things and persons, and the fear of living without the loved ones. He

concluded that when our life components mal-adjacent (the body and mind,

motor-perceptions and sensations, feelings and thoughts), they are painful.

Somehow our life has become maladjusted to our reality and this misbalance

obstructs our real happiness until it is overcome.

In order to heal the rupture, we need to know the cause of it.

The Second Truth identifies that the cause of the life’s misbalance is

desire (tanha). However, to shut down all desires in our

present state would be to die, and to die would not mean to solve life’s

problems. The Knowledgeable One explicitly admitted that such a desire as

liberation is necessary for the happiness of others. Therefore, only those

desires are bad that are directed for our private fulfillment. When we act to

benefit others, when we have altruistic desires, then we are free. However, that

is precisely where the difficulty is hidden – how to maintain that free state of

ours, because our selfish desire pulls us back from our freedom. Our egoistic

desire consists of all those inclinations, which "tend to continue or increase

separateness, the separate existence of the subject of desire; in fact, all

forms of selfishness, the essence of which is desire for self at the expense, if

necessary, of all other forms of life.... All that tends to separate one aspect

[of an organic unity, VS] from another must cause misbalance and suffering to

the unit... Our duty to our fellows is to understand them as extensions, other

aspects, of ourselves – fellow facets of the same Reality." Ibid. 91.

I could understand this as if I would hurt, for instance, my neighbor’s dog,

thus hurting my neighbor. The latter is a member of my community, which is a

unit of my society. Therefore, I would hurt my society and the society would

feel the pain, but I would not. Why? Because I would be the cause of misbalance,

but I would not be the effect of it and therefore would not suffer; the others

would suffer because of me. Buzz! Wrong thinking, would say the Knowledgeable

One. Where is the man who concerns in the same degree that the standard of

living for the whole world should be raised, as he concerns that his own salary

should be raised? Where is the woman who is as concerned that no one is hungry

as that she concerns about her own children? Here, said the Knowledgeable One,

is where the trouble begins; this is why we all suffer. Because if you, and he,

and she, and others would think like I just did, then not others but me, but all

of us, including me, would suffer. The difference would be that we would suffer,

but suffer not in the same time, not by the same cause, and not with the same

intensity. Instead of linking our hope and love to the whole unity, we persist

in attaching them to the tiny burros of our separate selves. Coddling our

individual identities, we lock our souls inside our egos and seek fulfillment

through their intensification and expansion. Then we suppose that this

imprisonment can bring our release and freedom. However, our ego is like a

hernia – the more it swells, the more it shuts off the free-flowing circulation

(on which our health depends), and the more our pain increases.

If the cause of the life’s misbalance and suffering is our selfish desire, then,

as the Third Truth states, our cure is in our overcoming of such

selfishness. If we could be released from the narrow borders of

our self-interests into the vast universe, we would be relieved from our

torments.

The Fourth Truth follows as – the overcoming of the selfish desire (the way out

of our captivity) is through the Nine-Lane Highway

2) The Nine-Lane Highway

The Knowledgeable One approached the problems of life like a physician, starting

from a careful examination of the symptoms that provoked the patient’s concern.

If everything would go smoothly and freely, then the patient-to-be would not

worry about his life’s process as he would not usually worry about his digestive

process, and there would be no necessity for the Knowledgeable One’s advice and

diagnosis. However, this is usually not the case. The patient usually comes with

more pain, more conflict, and less freedom than he should have. Therefore, his

life is out of joint – misbalance.

Then the Knowledgeable One asked, what is causing these abnormal symptoms? Where

is the nidus of the infection? What is always present when the suffering occurs;

is it absent when the suffering is absent? When the particular selfish desire,

which caused misbalance, is determined; then, it can be overcome. How it

should be overcome – by riding through the Nine-Lane Highway, a course of